Design for Social Impact

An earlier blog post talked about MODA's 2011 move to Atlanta's Midtown Arts Corridor and how that move pressed the reset button on an organization that was two decades old. After the move, in late 2012, in an effort to answer the question, "what is a design museum," MODA established a new mission and vision. In the process of writing these foundational statements, the board of directors and staff also worked together to establish a definition of design that would guide operations at the museum. That definition — which establishes design as a process found at the intersection of creativity and functionality and as a process that can solve problems, transform lives, and make the world a better place — now guides all decisions about programs and exhibitions made at MODA.

Because exhibition calendars are built out months or years in advance, it took us until 2014 to curate the first exhibition in which we tried to embody our definition of design. We did so with an exhibition called Design for Social Impact, that was curated by Katie Simms and designed by Chris Livaudais and his team from InReality.

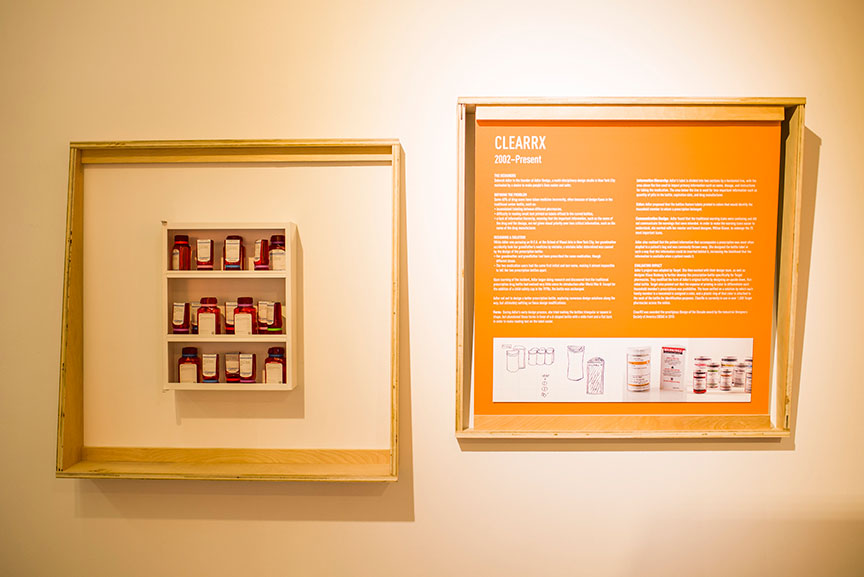

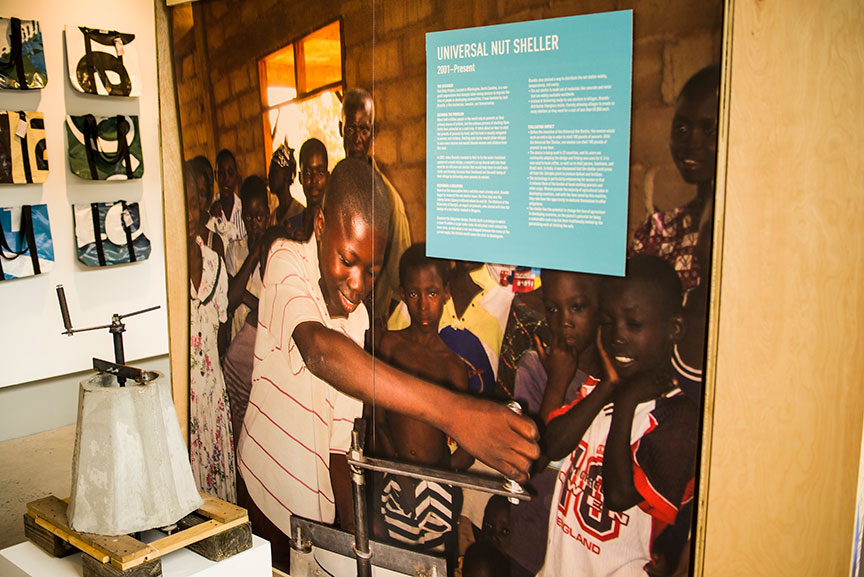

With Design for Social Impact, our goal was to explicitly showcase design as a creative problem solving process that can solve problems, transform lives, and make the world a better place. In order to do so, the exhibition presented 24 case studies — each an examination of design processes used by students, design firms, non-profit organizations, or large corporations to address contemporary problems such as homelessness, energy production, infant mortality, and access to clean water.

Visitors to the exhibition were introduced to human-centered design and design thinking through a case study examining the design of the popular OXO Good Grips kitchen tools. Some of the other projects showcased — like the Embrace Baby Warmer — were examples of how students are using the design thinking process to address challenges worldwide. Other projects show were lesser known because they were just hitting the airwaves in 2014, like the SafiChoo Toilet designed by three women who were Georgia Tech students (which has now evolved into a project called Wish for Wash). And, others, like the Net-Effect project by Interface, were designed by large corporations seeking to have positive social impact in the world.

Design for Social Impact was a big success. It was one of MODA's best attended exhibitions and received positive responses from visitors from the day that it opened. But, I found the exhibition strangely unsatisfying. Though we had put up an exhibition that effectively embodied the museum's newly-established definition of design, it didn't seem very different from past exhibitions. To my mind, something was not right.

It took a while to figure out what was bothering me, but when I did, it was as if a ton of bricks fell on my head. We'd put up an exhibition that positioned visitors as outsiders, that asked them to passively admire the work of others. Theoretically, there was nothing wrong with that: the model is a tried and true one used by museums worldwide. But, it set up a duality that was not in keeping with the processes and projects on view: MODA and the designers we had chosen to feature were positioned as authority figures or keepers of knowledge, while visitors were invited to view processes and their outcomes from the outside. The traditional form of this exhibition was not appropriate for content that celebrated the power of individuals and groups — some Designers and some not — to use design as a creative problem-solving process to address real-world challenges.

So, I began to ask myself a lot of questions — and I continue to do so and have shared my questions with MODA's staff and board and many others: Is design a process that's only effective when used by Designers or can it be used in powerful ways by non-designers? Can MODA's exhibitions actively involve visitors in the design process and empower them to use this form of creative problem-solving (or elements of it) to address real world challenges? Can a design museum change the world?

I don't have answers to these questions — they are a framework for my work and much of the work done at MODA. Most likely, we will never have solid, concrete answers to these questions, but they're allowing us to explore what it means to be a museum in the 21st century and to think about how a small, non-collecting institution can have significant impact on the community it serves.