Design for Healthy Living

A year or so after the Design for Social Impact exhibition provoked me to start thinking about how a design exhibition could actively involve visitors in design processes that address real-world problems, we produced an exhibition titled Design for Healthy Living that was another attempt to integrate visitor participation in design processes into the museum exhibition experience. On the surface, this challenge seemed straightforward. In reality, it has proved to be extremely difficult and I do not feel satisfied that we have met the challenge effectively yet.

But, Design for Healthy Living was an important step in our still-ongoing exploration. The exhibition — which was curated by Katie Simms and designed by Susan Sanders and Hannah Horrom — explored the impact of the built environment on human health and presented specific design strategies used to promote routine physical activity and healthy living.

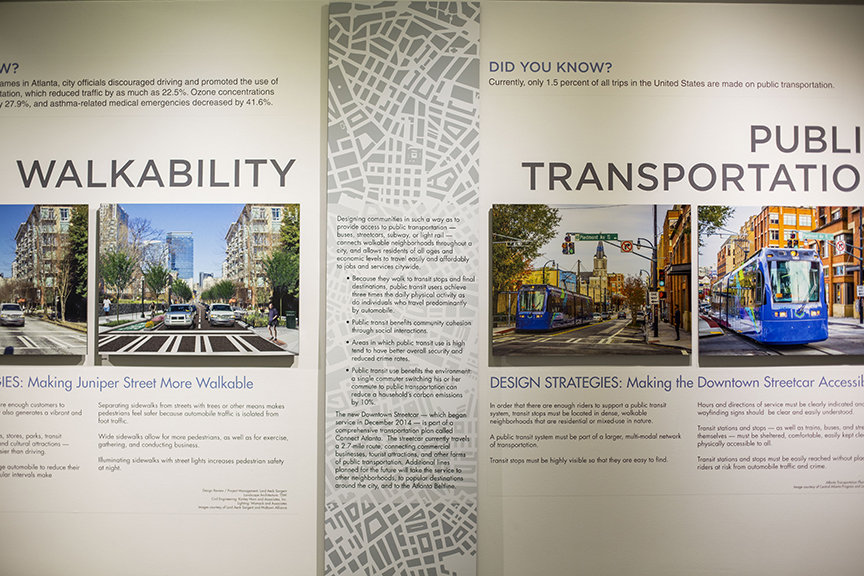

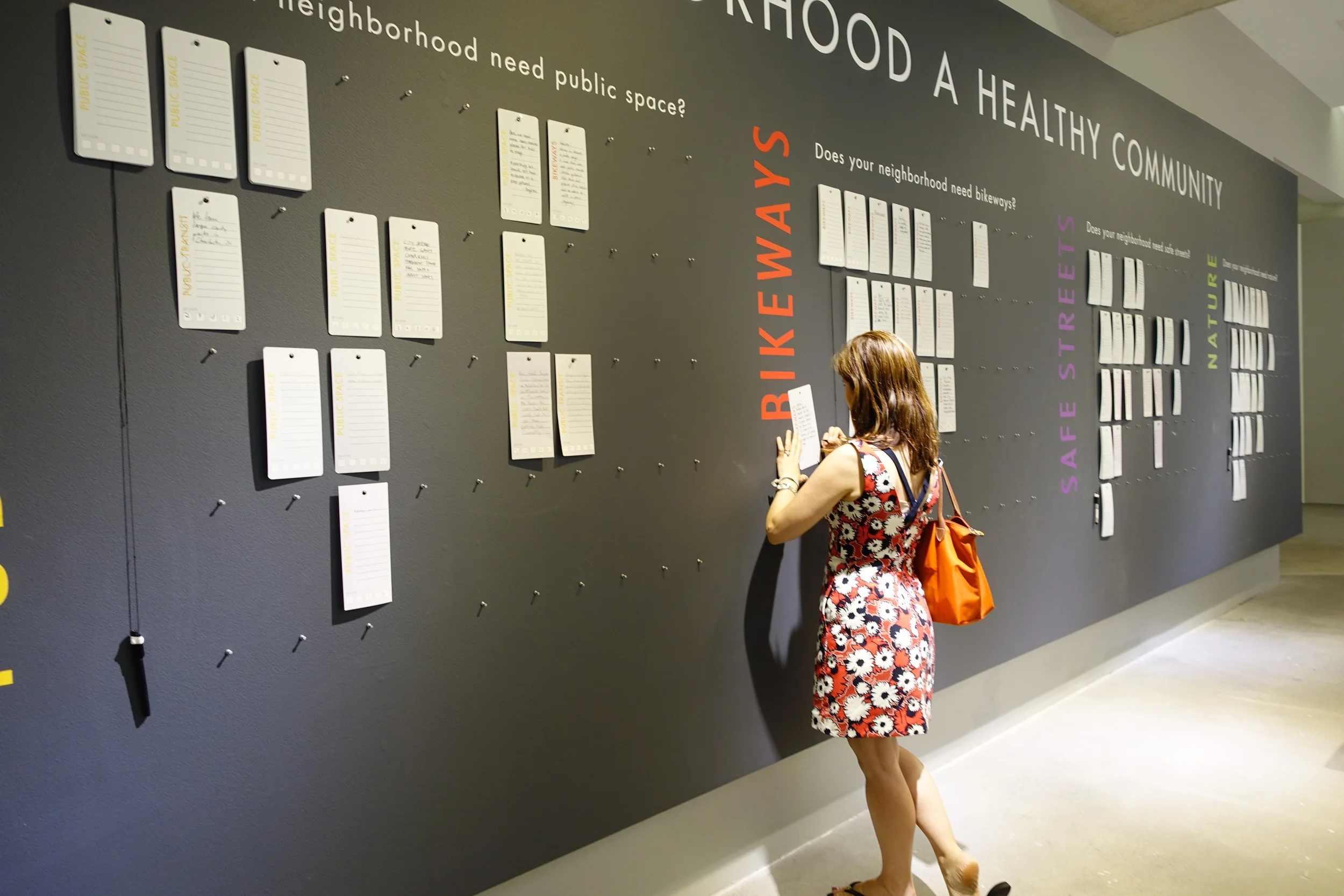

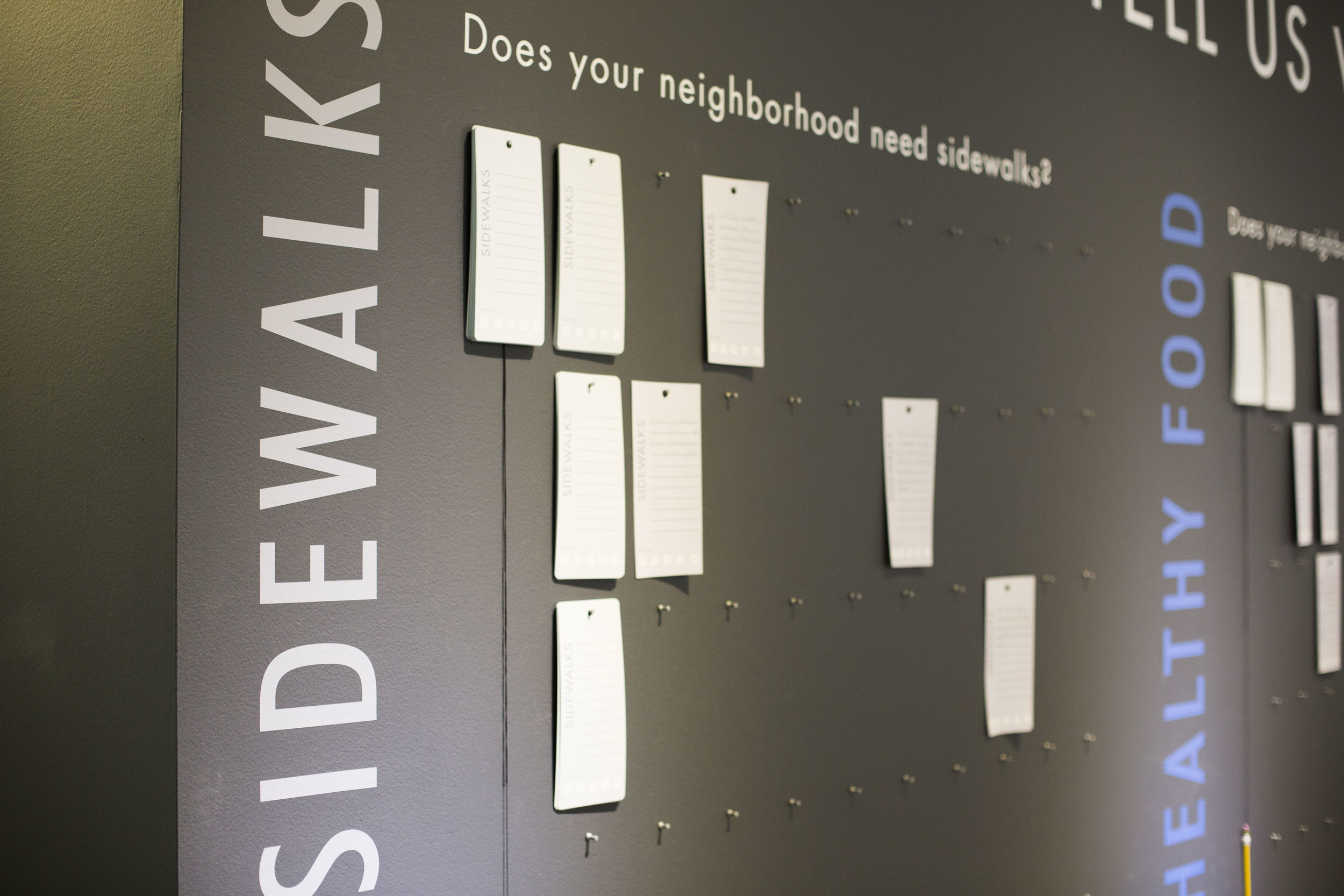

One one side of our hall gallery (see photos below), we asked the question, "what does an urban built environment need in order to promote health?" In answer to that question, we identified seven health-promoting conditions that can be designed into a city: walkability, public transportation, bike-ability, safe streets, access to nature, access to healthy food, and access to public space. Text panels explained why these conditions are important, discussed design strategies for creating these conditions, and provided positive examples of ways in which these attributes are being designed into specific parts of the metro community. We hoped that by presenting this information in a manner not unlike an Urban Planning 101 textbook, visitors could leave the exhibition armed with the knowledge and language they need to advocate for positive change in neighborhoods and communities.

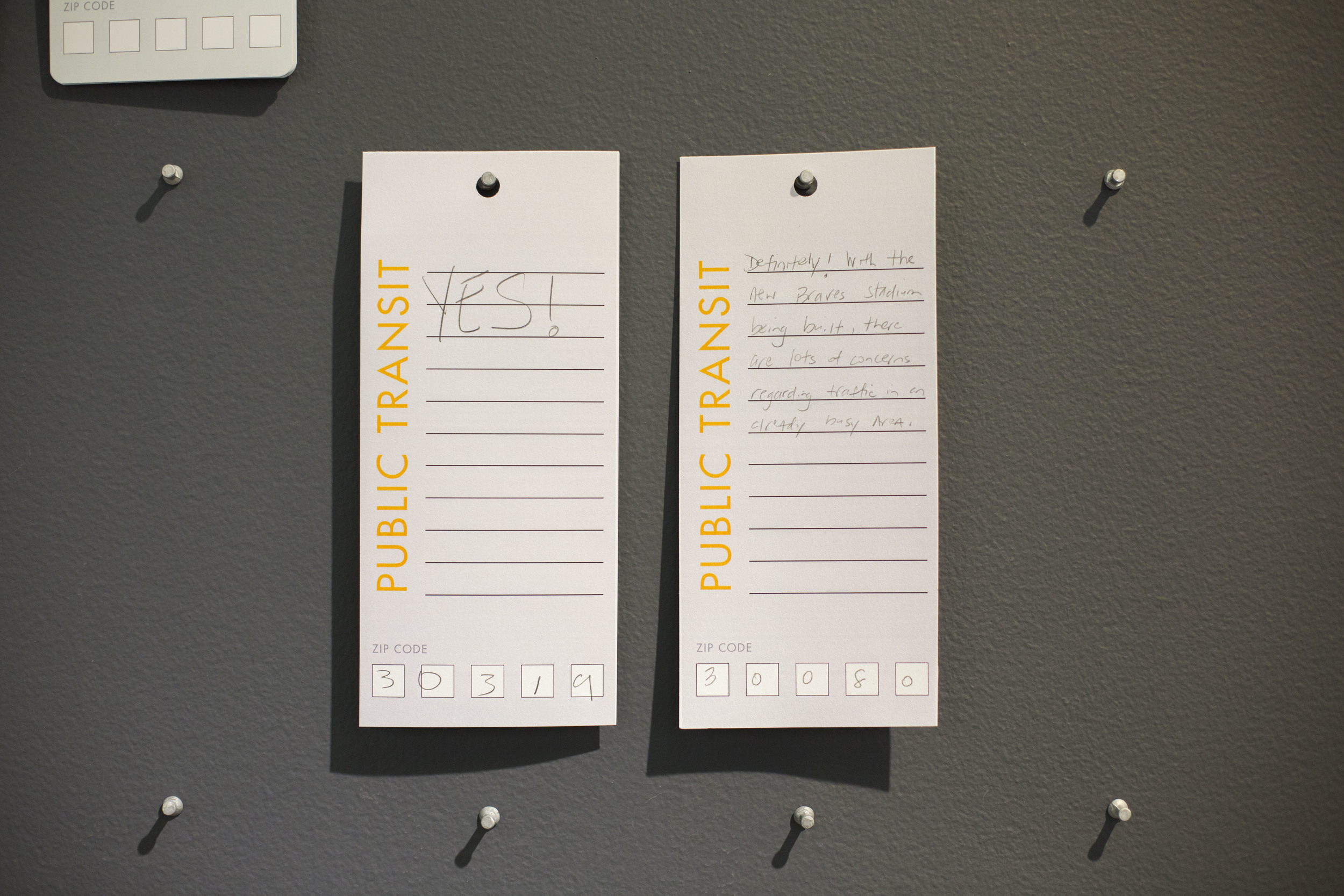

But, we understood that asking visitors (even those who entered the museum already invested in the design of healthy living environments) to acquire knowledge and language and then find time and motivation to use it outside of the museum was asking a lot. And, we understood that visitors who were inspired by what they learned might having things on their mind that they'd want to express right away. So, we dedicated the other side of our hall gallery to collecting information, i.e. gathering the kind of data that might allow identification of urban design challenges throughout the city. Who knows the problems of a community or neighborhood better than the residents who face them on a daily basis? To this end, we asked seven questions that corresponded with the seven attributes of a healthy community that we'd identified:

- Does your neighborhood need sidewalks?

- Does your neighborhood need access to public transport?

- Does your neighborhood need bike paths?

- Does your neighborhood need safe streets?

- Does your neighborhood need access to nature?

- Does your neighborhood need public spaces?

- Does your neighborhood need access to healthy food?

Visitors were invited to take a blank card from a the wall, to write their answers on the cards and to identify their home locations with their zip codes. We gathered hundreds and hundreds of responses — most passionate and sincere — and we hoped that we'd be able to share this information with neighborhood planning units and other organizations working to improve communities across metro-Atlanta. Quickly, we learned that we should have used a different form of geographical identifier, however. Five digit zip codes are very broad identifiers, making it difficult to effectively share the information we gathered. We were disappointed, but understood that we have a lot to learn as we innovate ways of involving visitors in design processes.

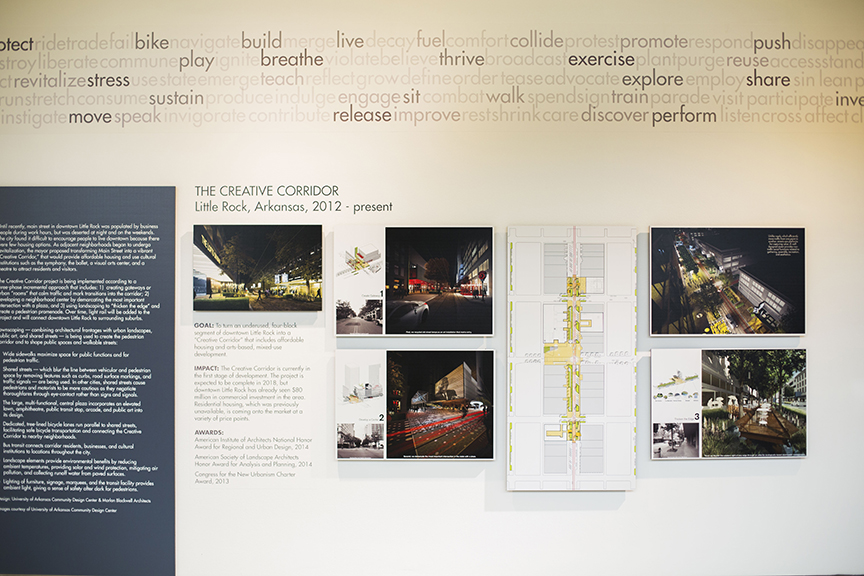

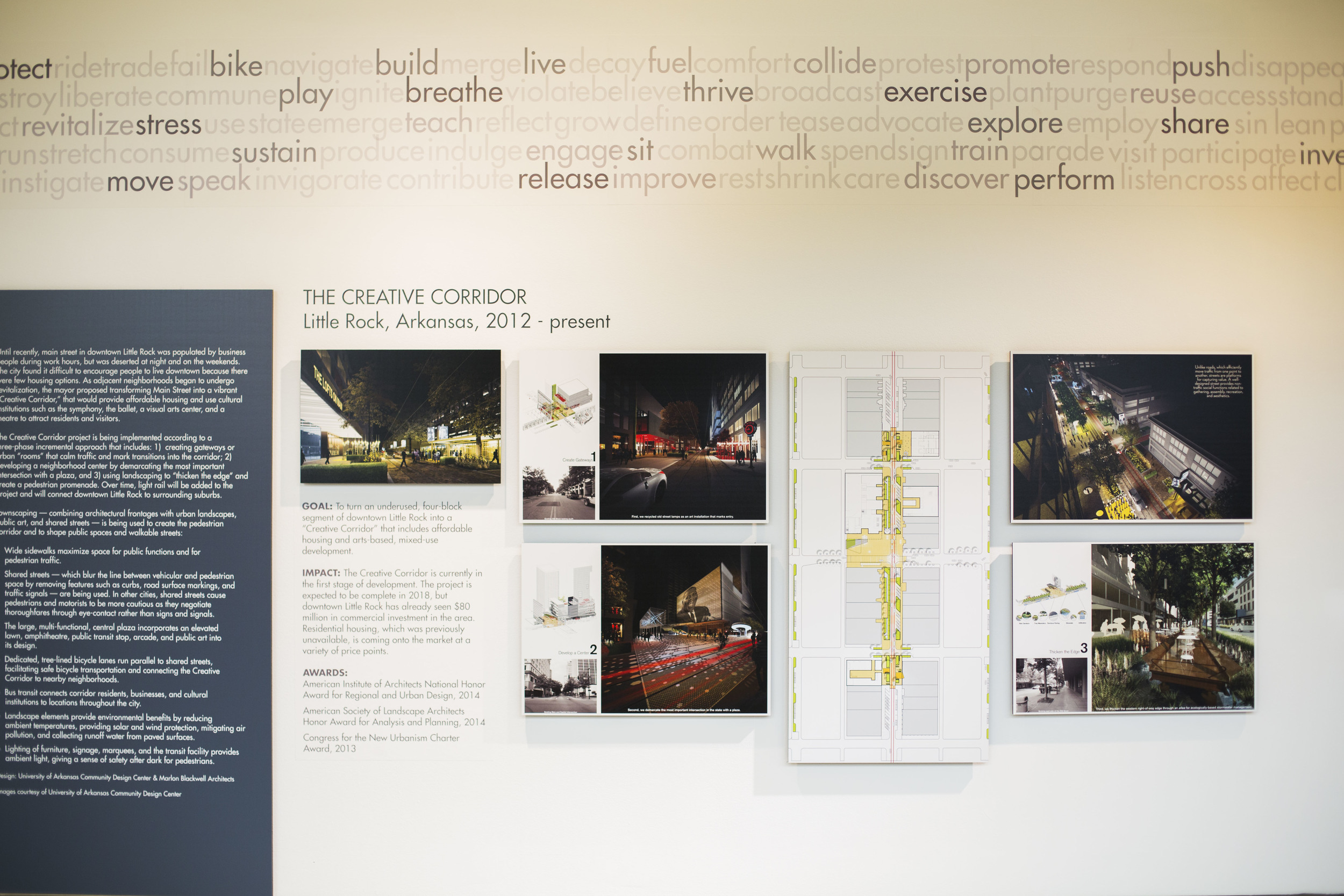

Our back gallery provided case studies of built environments from across the nation that successfully promoted health through their design, including schools, office buildings and other kinds of work environments, downtown districts, hospitals, and other types of projects that are common in cities everywhere. Here, our goal was to demonstrate a variety of model projects in which the seven attributes of a health-promoting built environment identified in the hallway were used together to design a building or area that protected and promoted health.

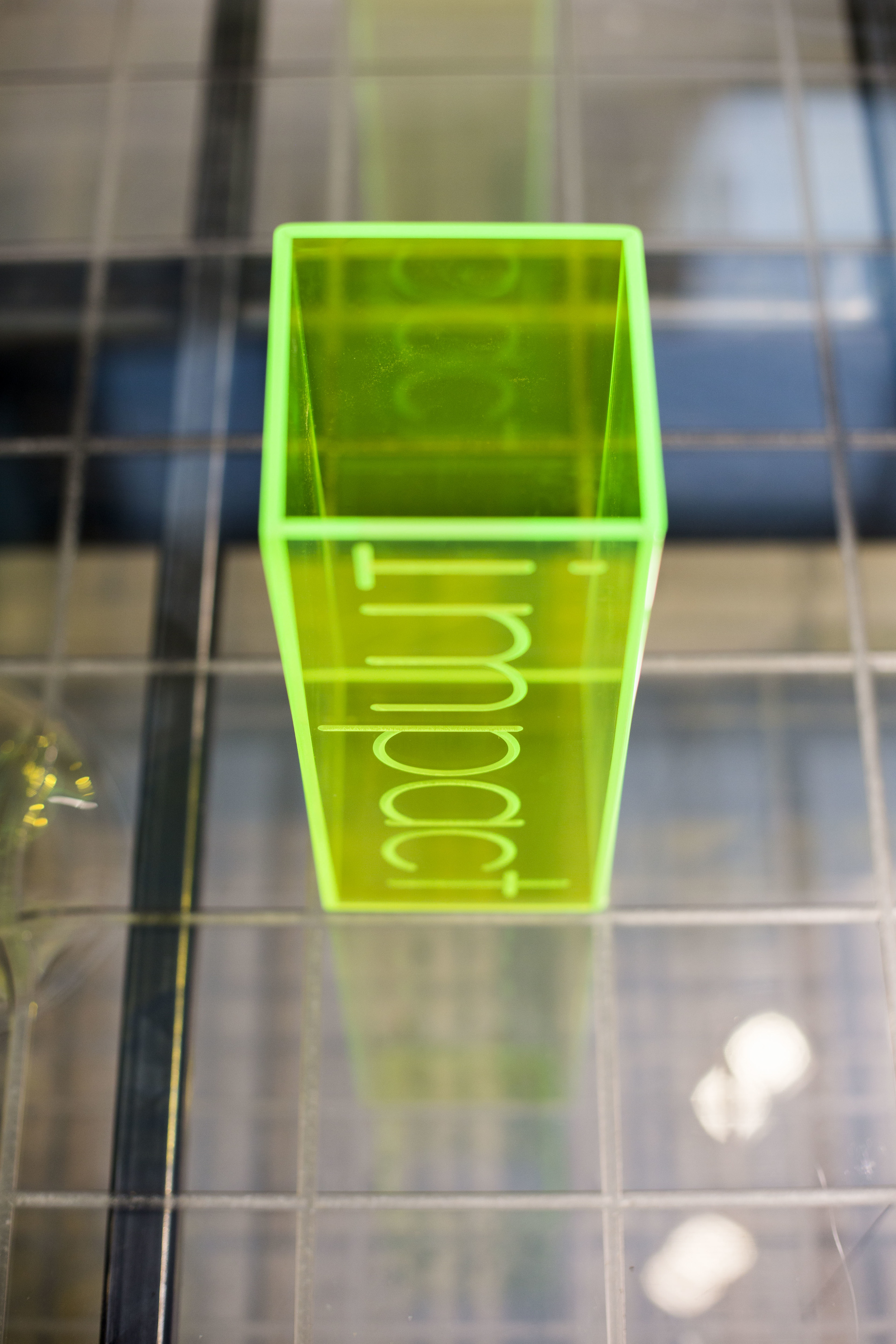

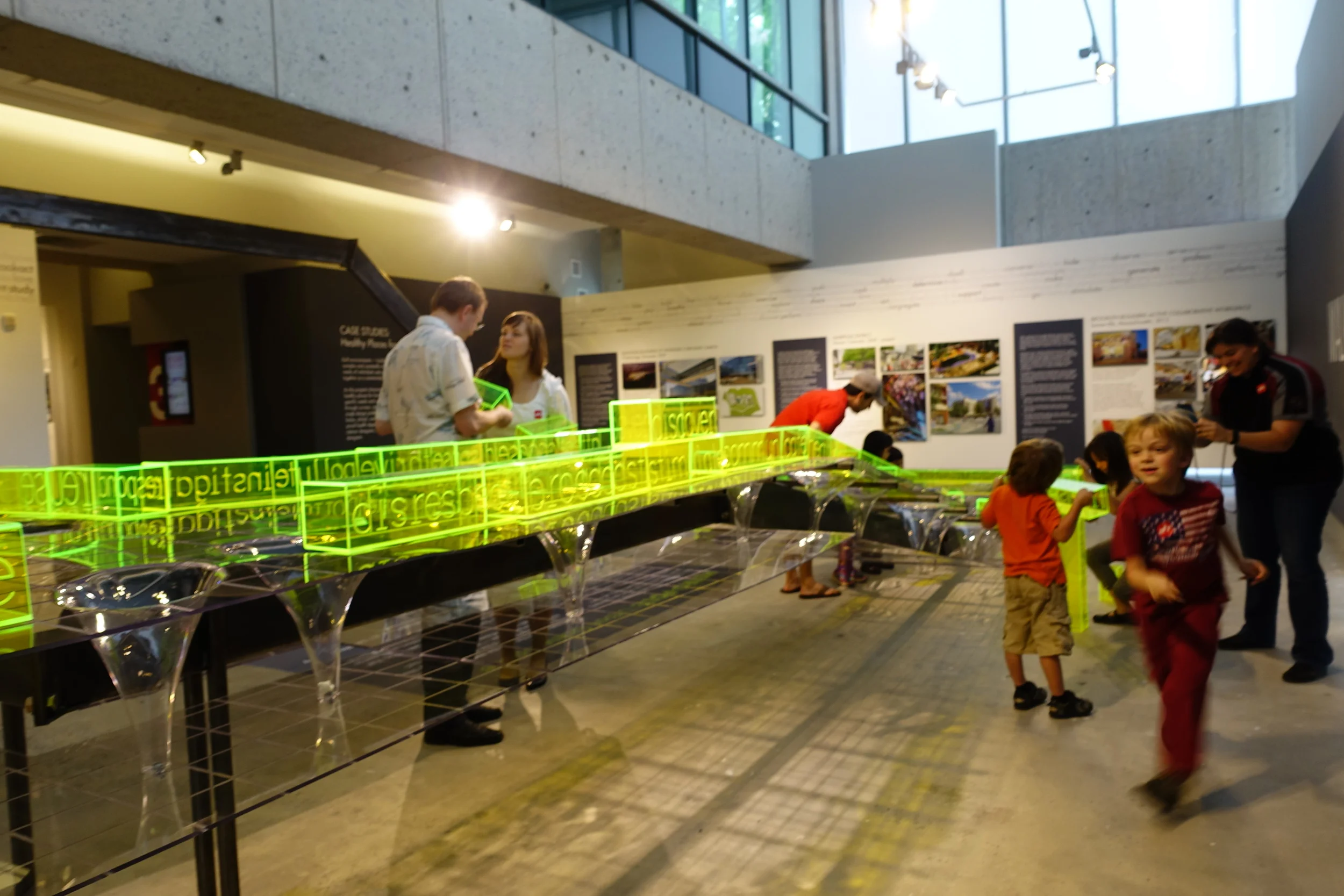

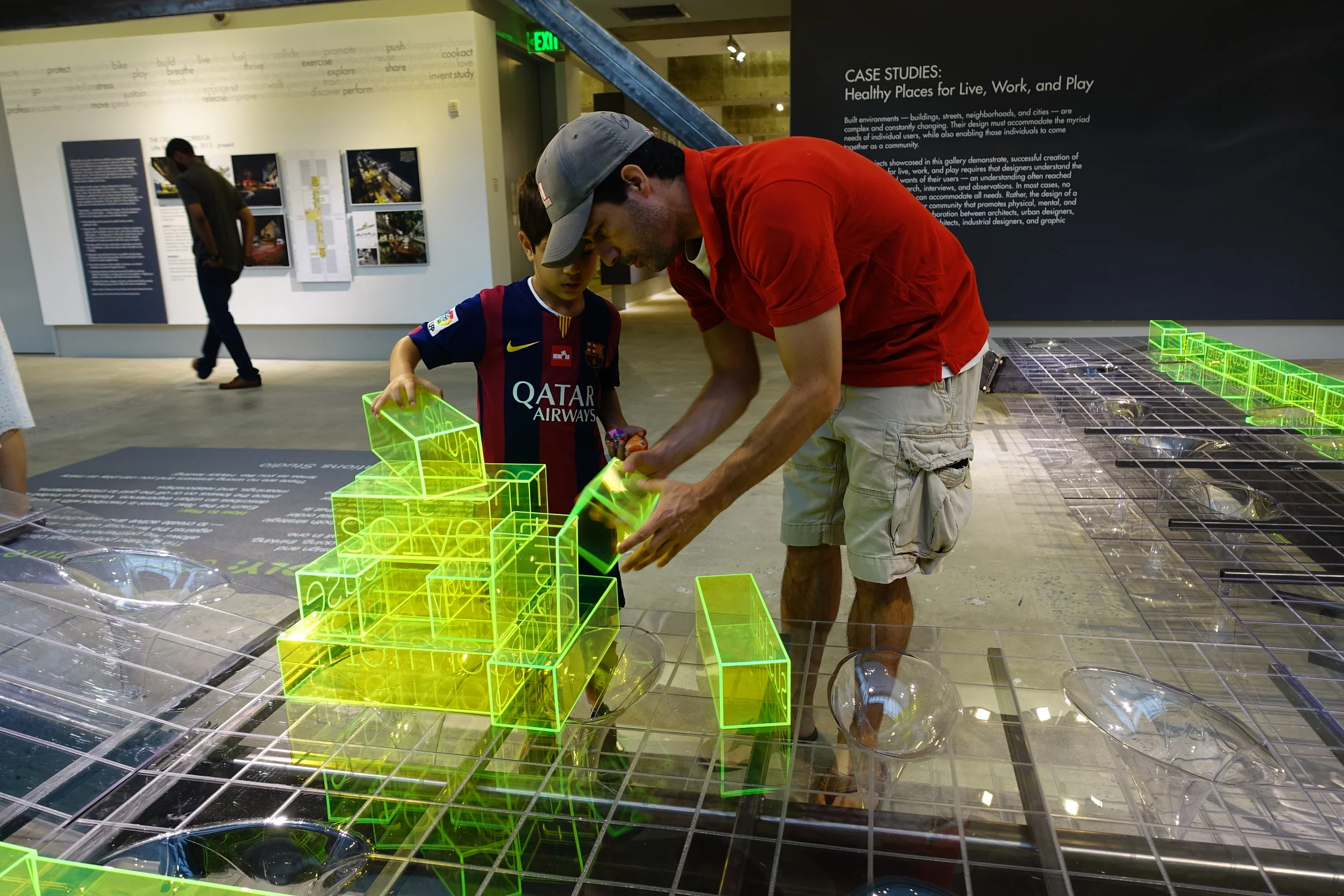

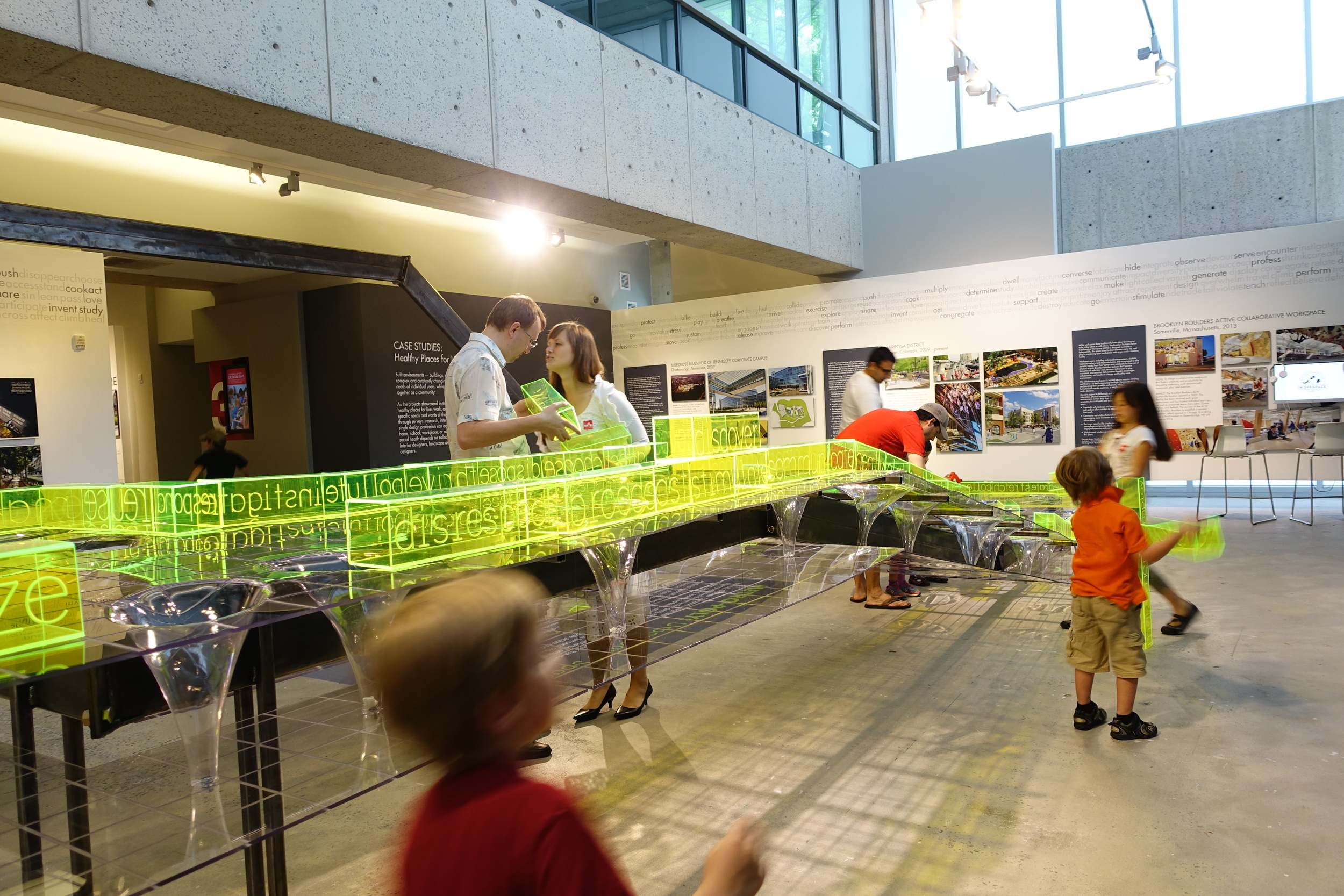

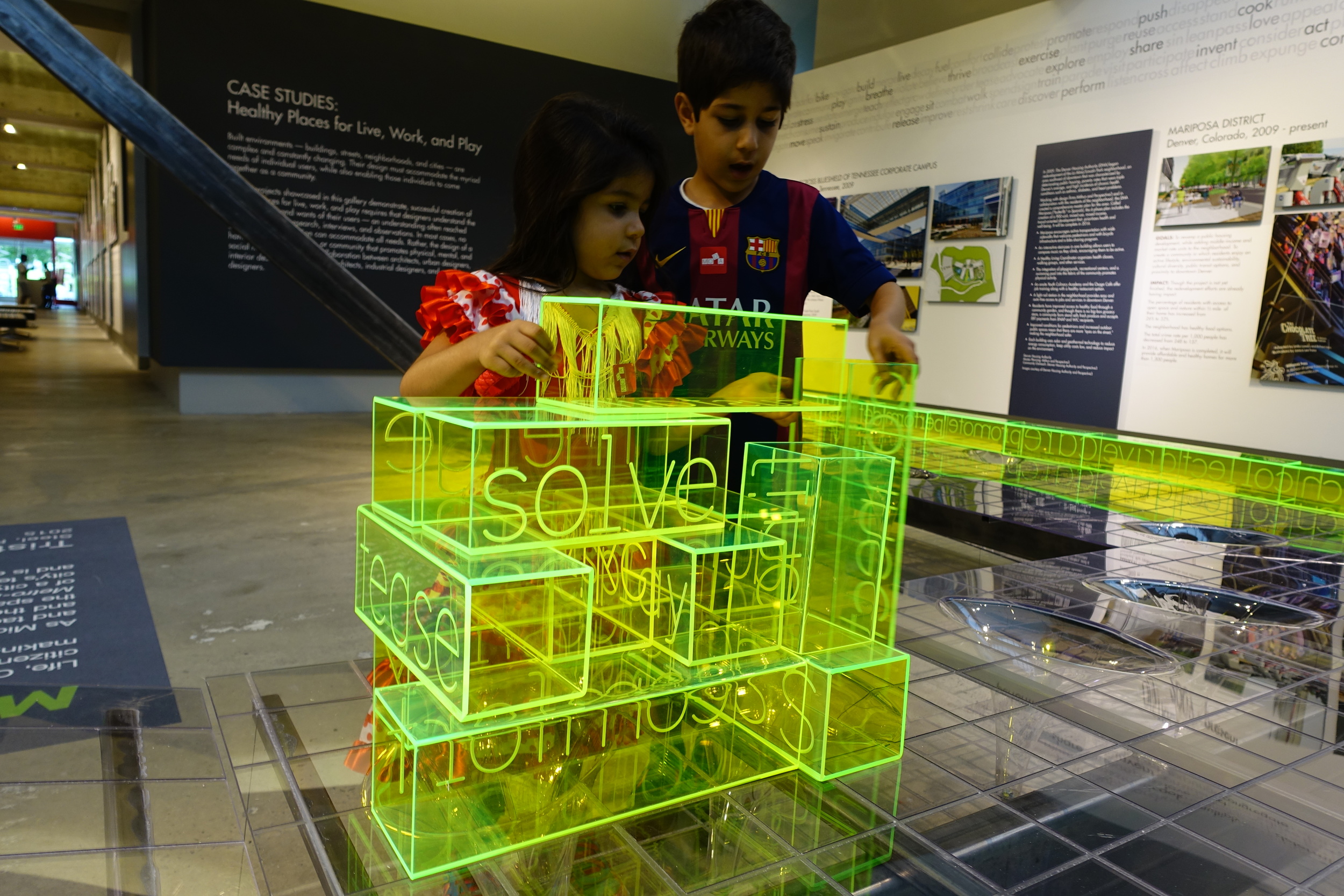

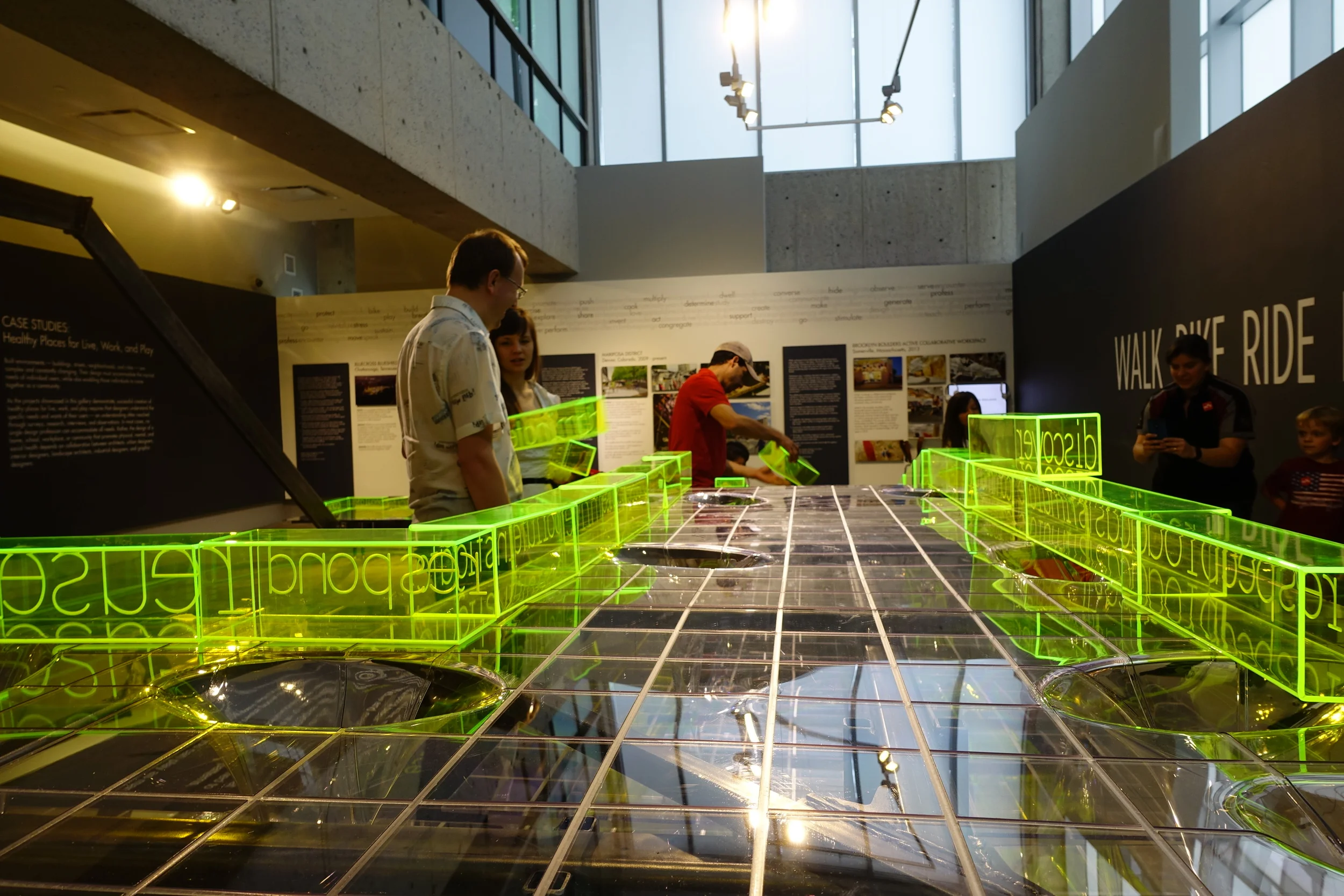

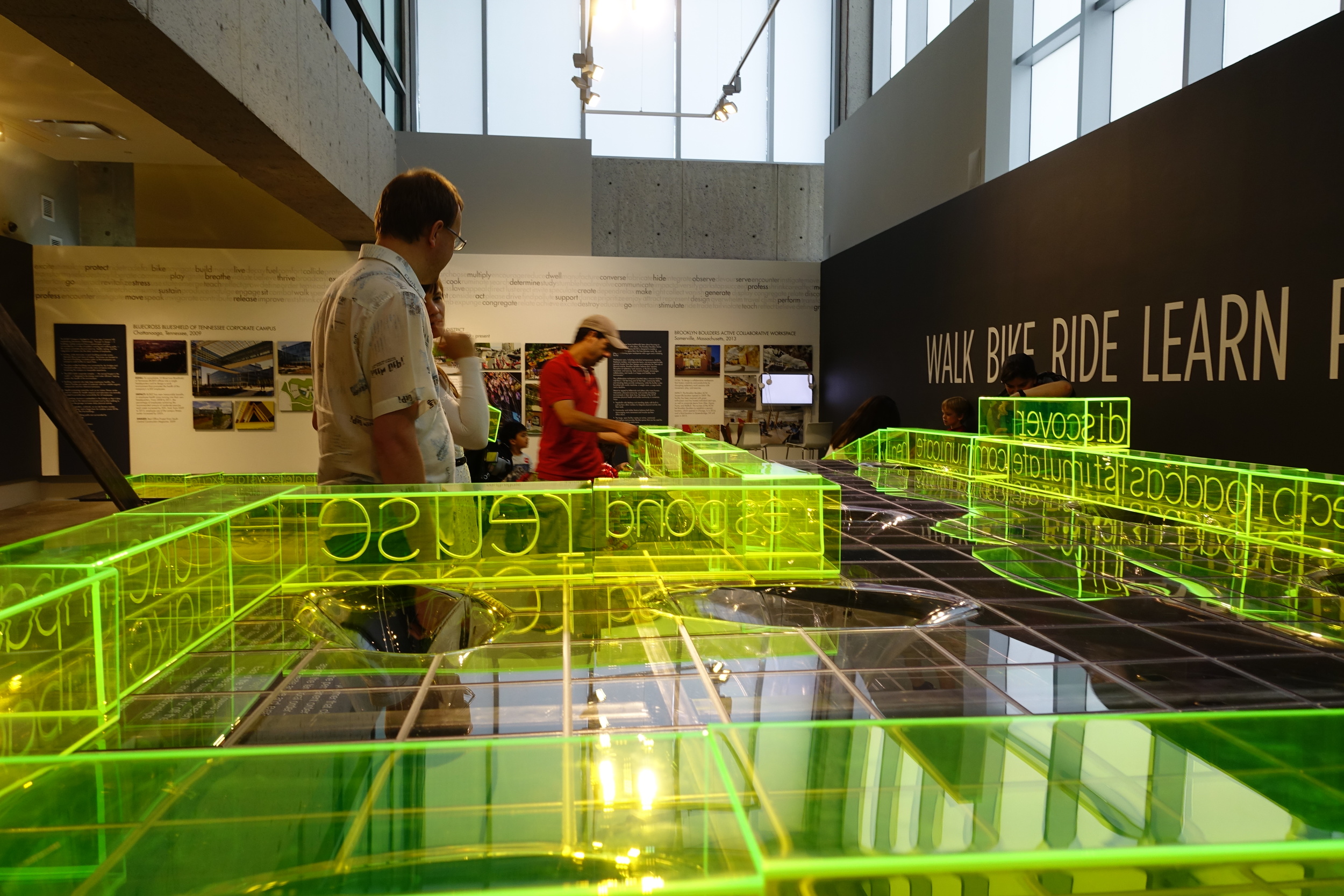

While the case studies were a more traditional museum presentation, the center of the back gallery featured a wildly-popular interactive installation by artist and designer Tristan Al-Haddad of Formations Studio. Commissioned by MODA for this exhibition (see photos below), the installation was an urban game space called Metro-Poly made of steel, plastic resin, and acrylic. It consisted of a gridded polymer surface that was supported by an over-scaled steel structure. Together the steel structure and the gridded polymer surface represented the permanent order of a city. Text Towers — acrylic towers inscribed with verbs describing the wide variety of actions that city dwellers engage in daily — rested on the gridded polymer and could be moved according to visitors' will, allowing permanent order to rub up against temporal actions and create unexpected urban juxtapositions.

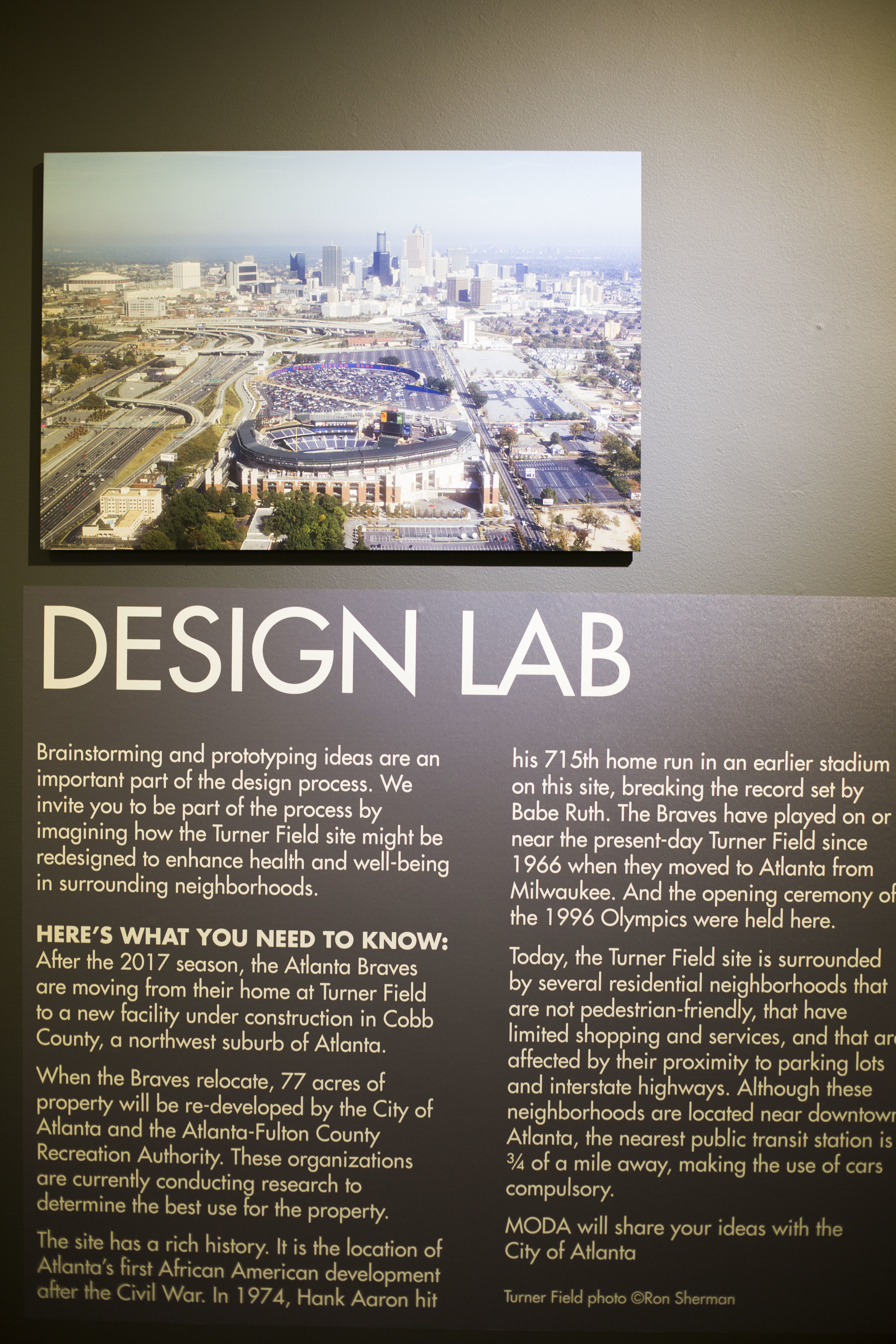

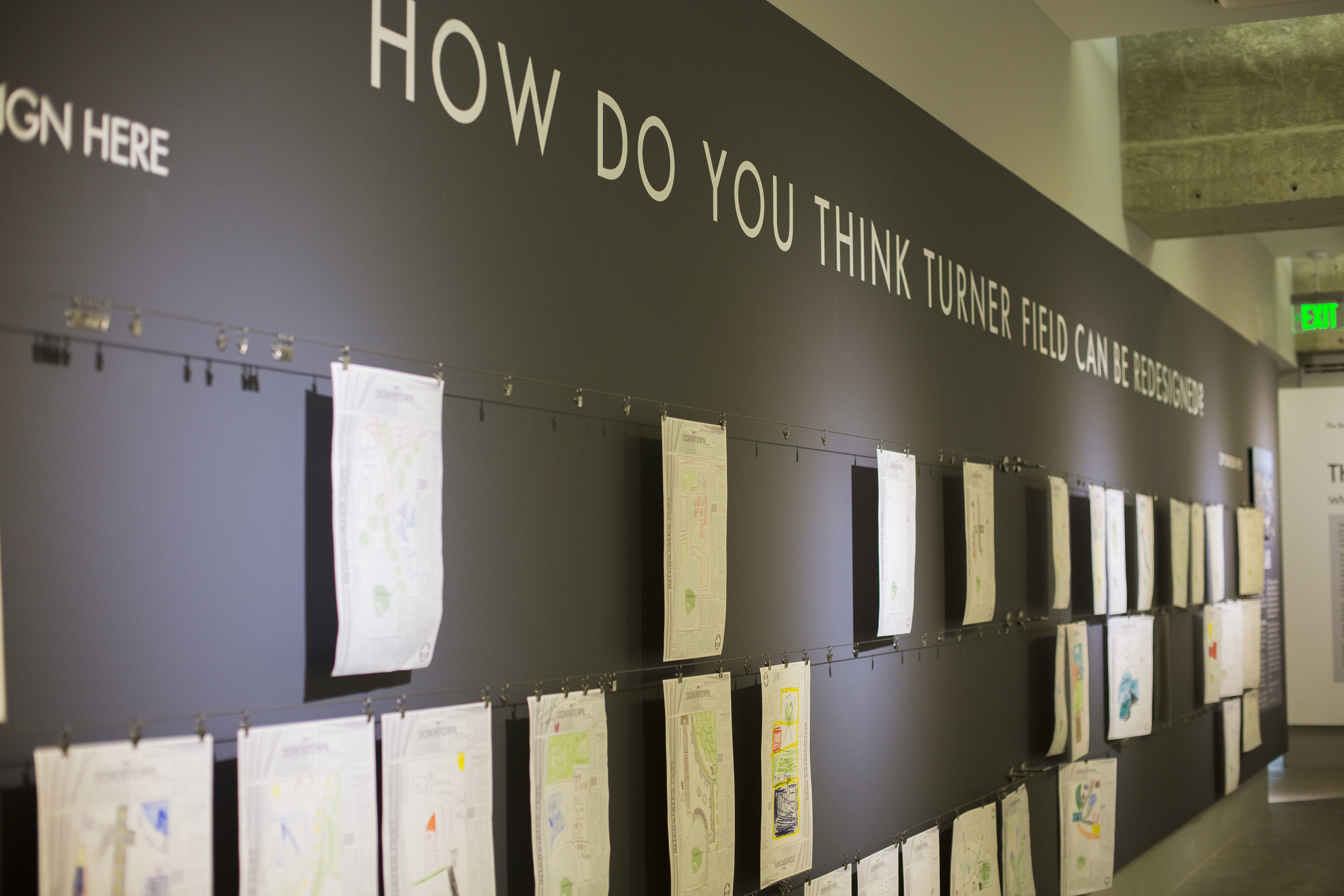

Our side gallery addressed two major urban design projects currently underway in Atlanta: the Atlanta Beltline, a 22-mile loop of old railroads encircling downtown Atlanta that connects 45 neighborhoods (this article effectively discusses the importance of this project in the context of current attitudes toward urban design projects nationwide) and the re-development of Turner Field as the Atlanta Braves plan their controversial departure from their long-time downtown venue for one currently under development in the northern suburbs of the city.

The Beltline was treated in a traditional fashion with text panels that explained the project and its potential impact on the city in terms of the physical health of individual residents and the fiscal health of the city as a whole. But, because the Turner Field project was very much the subject of controversy at the time of this exhibition with everyone in the city debating the nature of the site's redevelopment, we asked visitors to get involved.

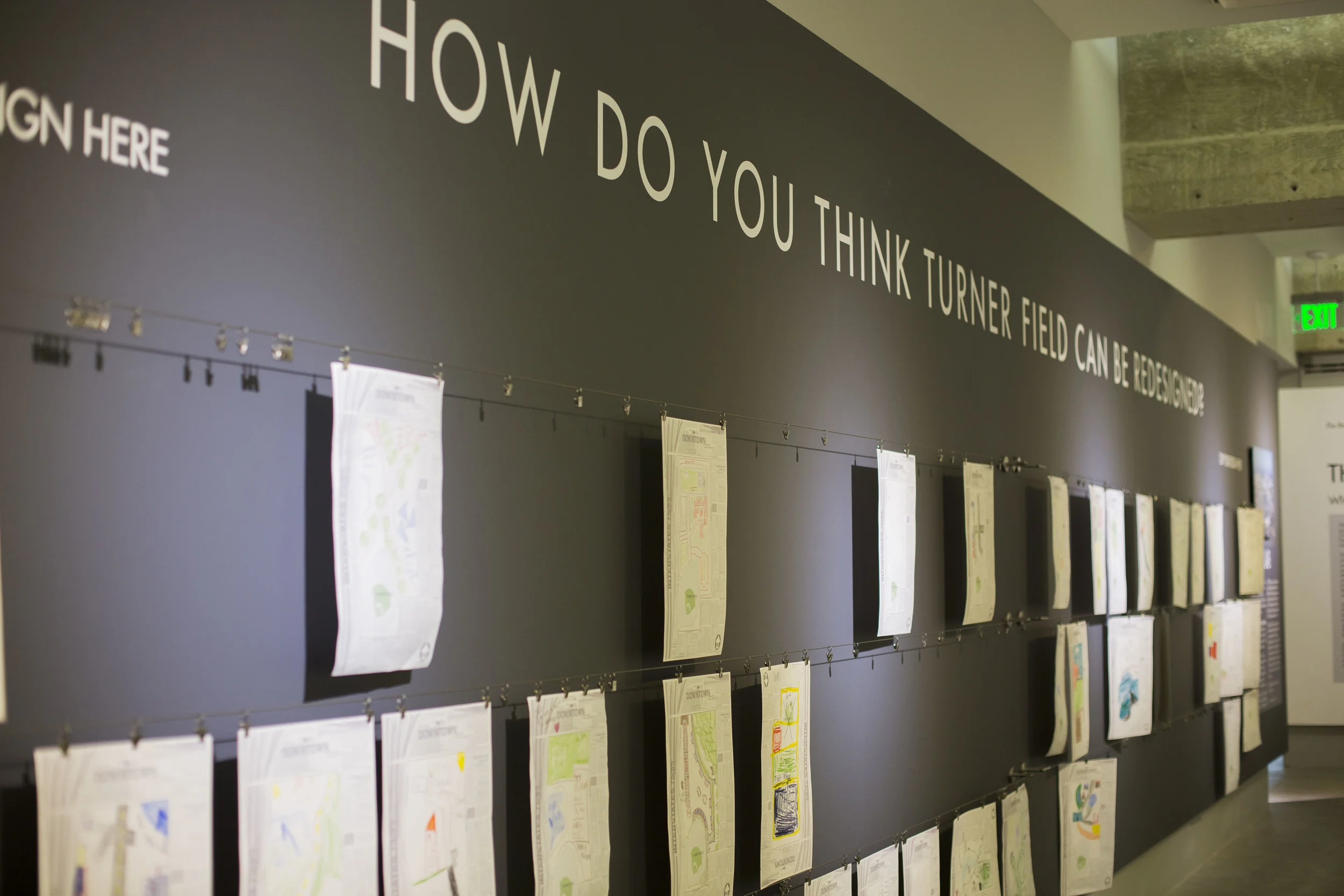

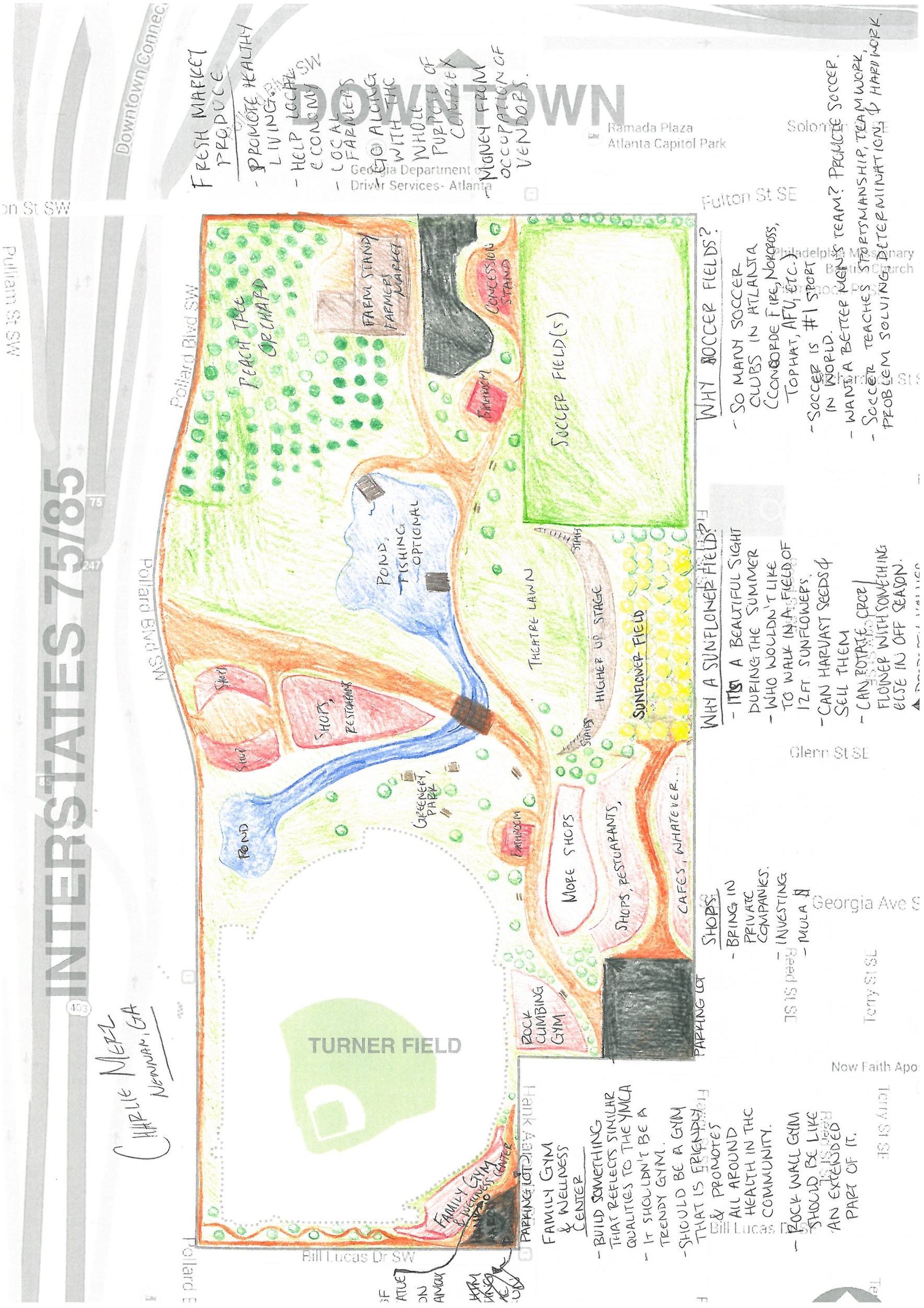

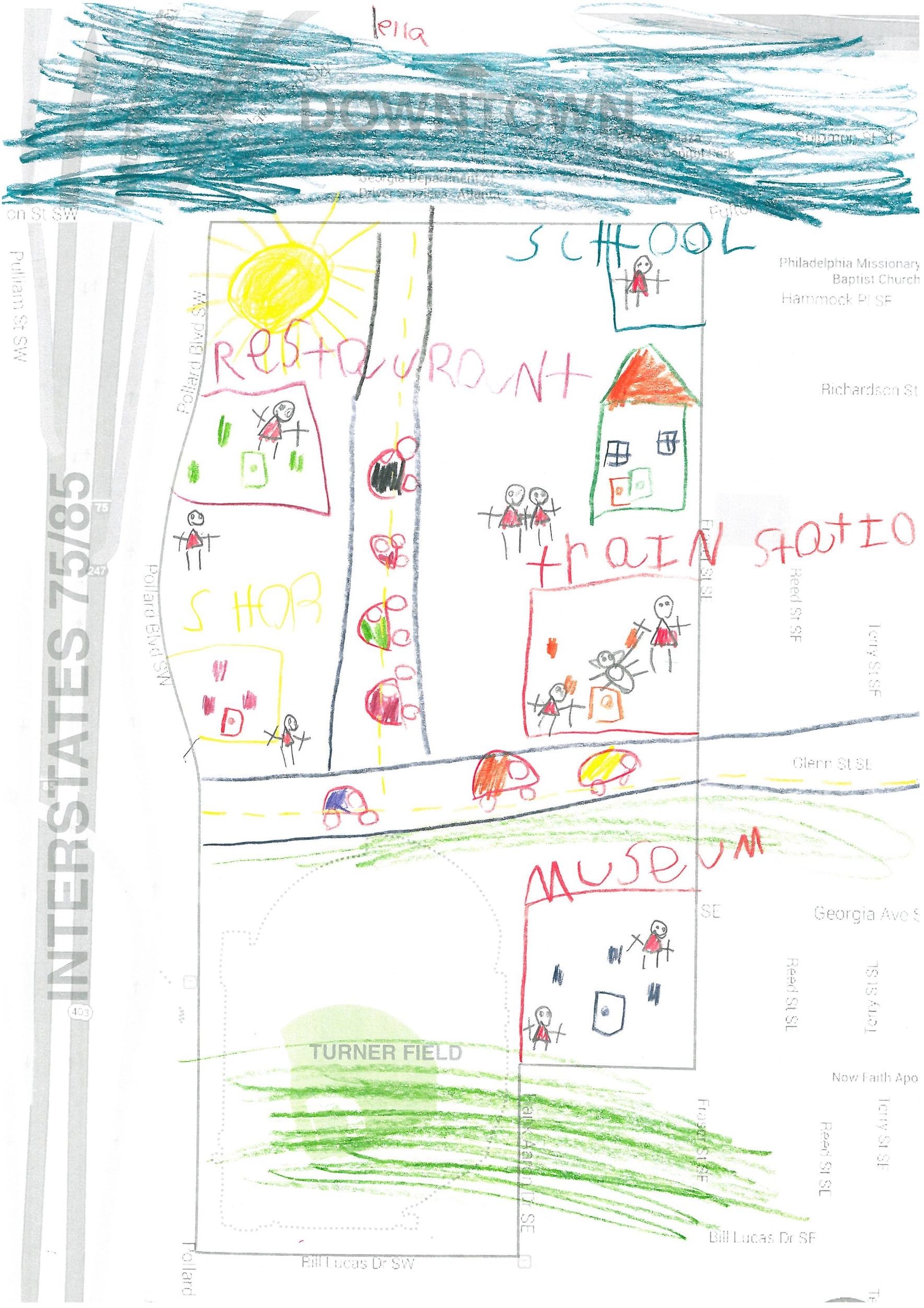

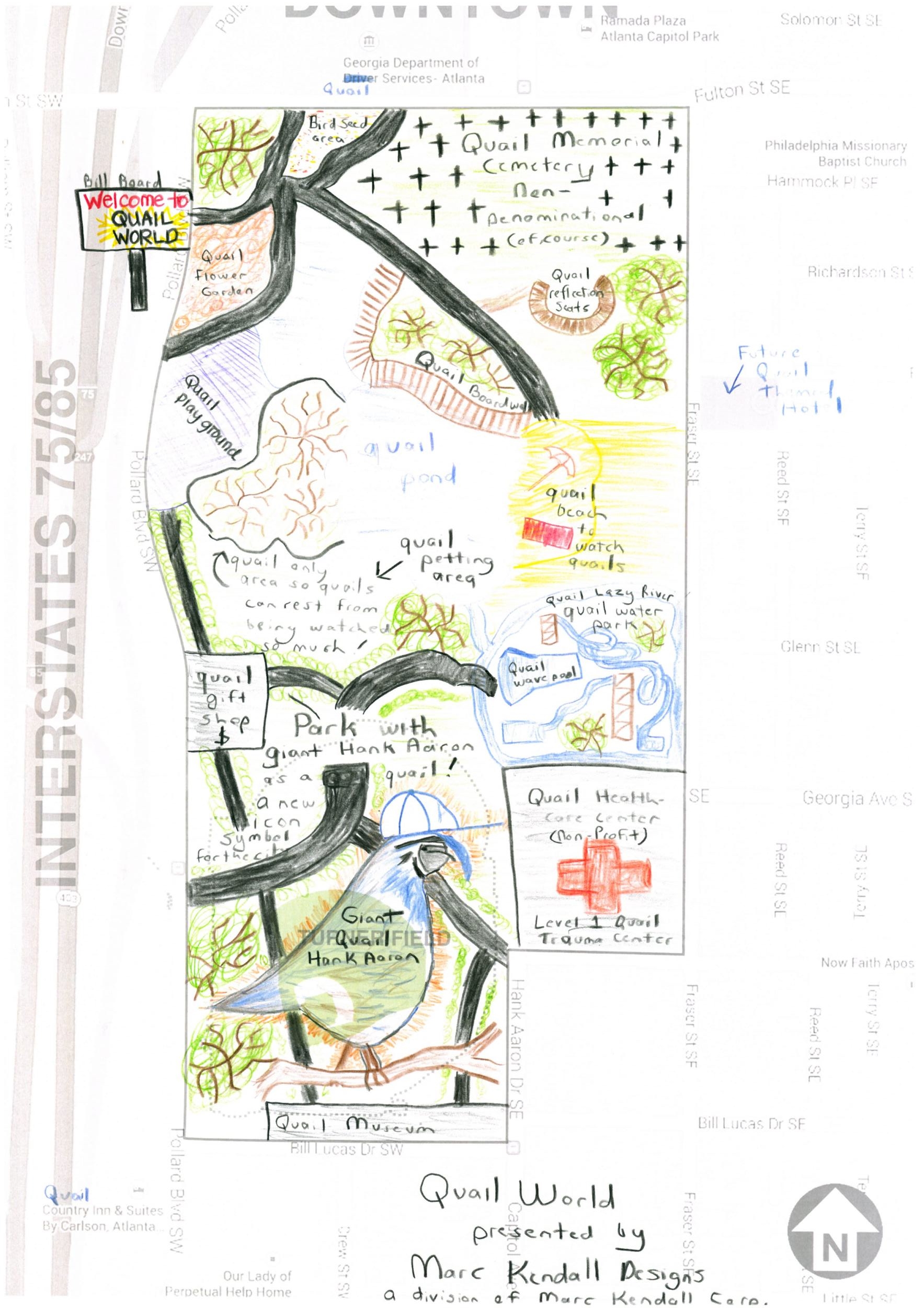

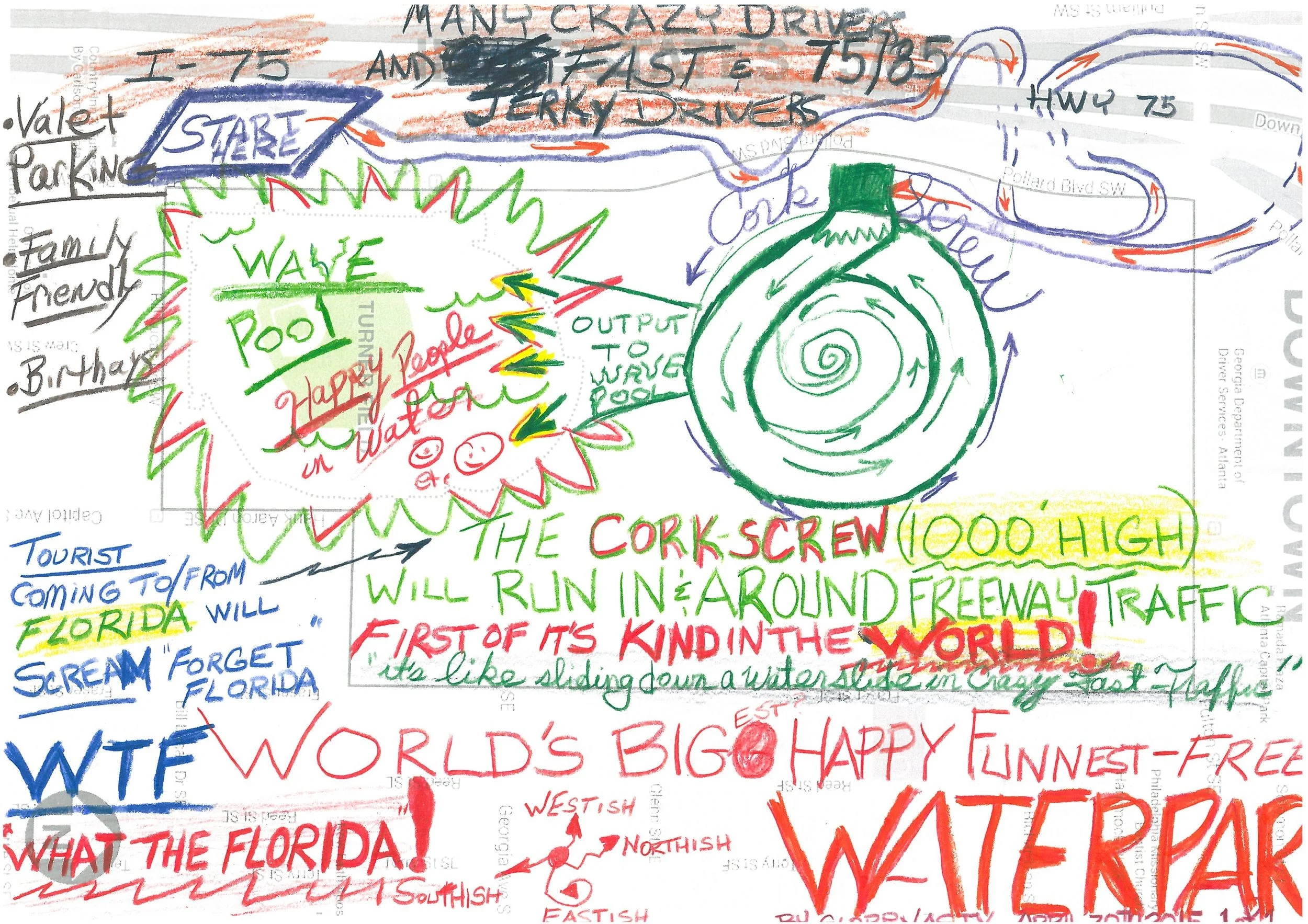

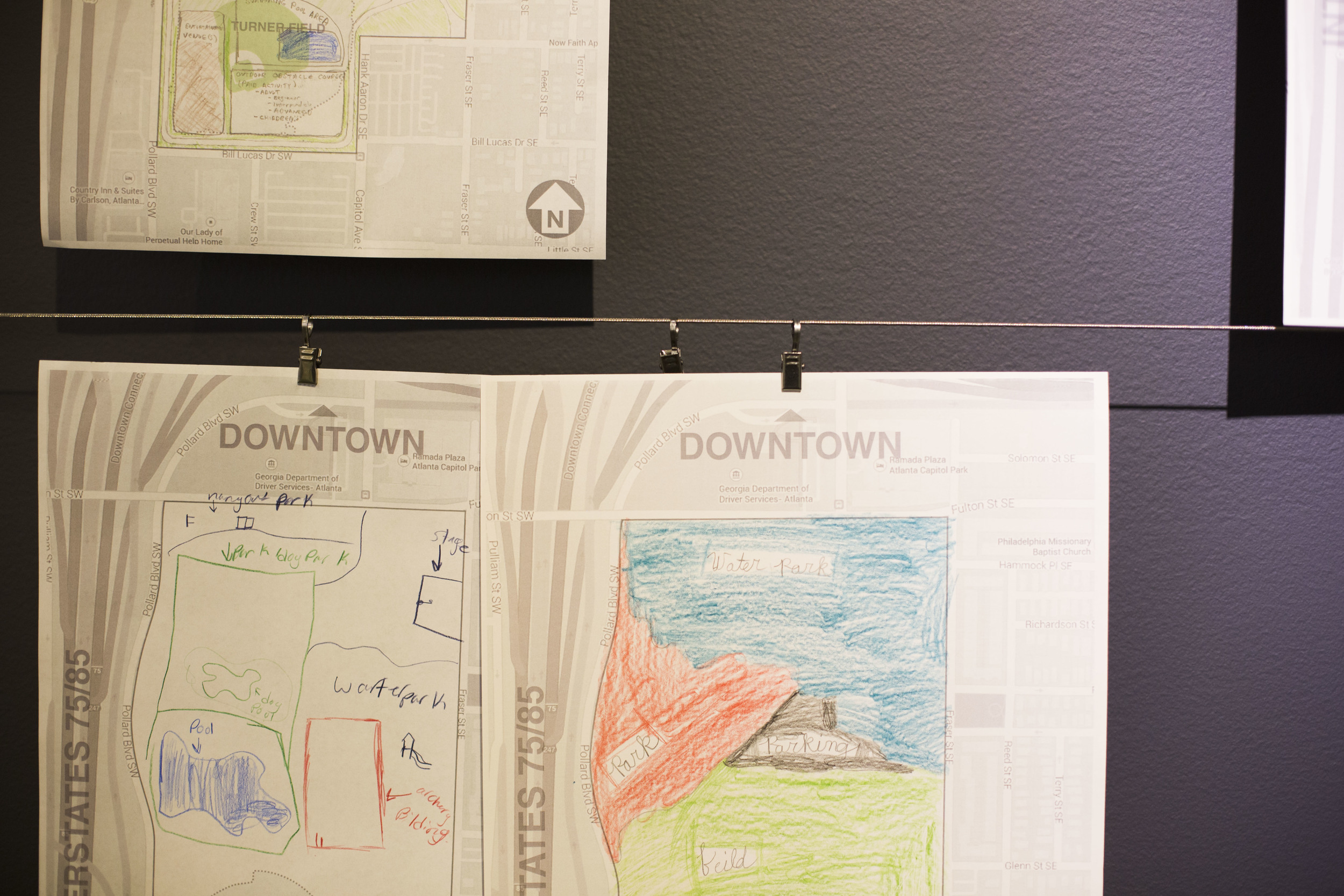

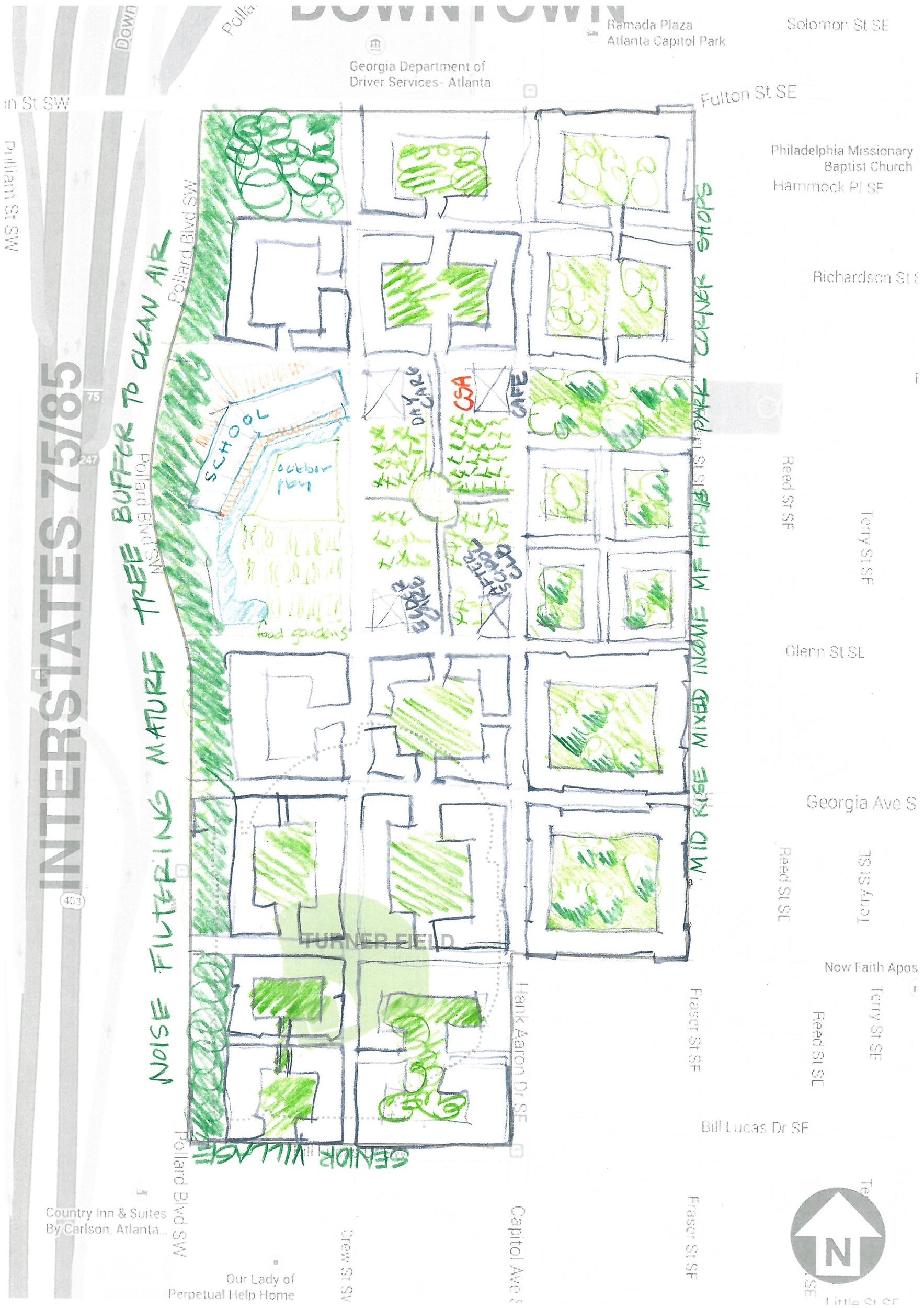

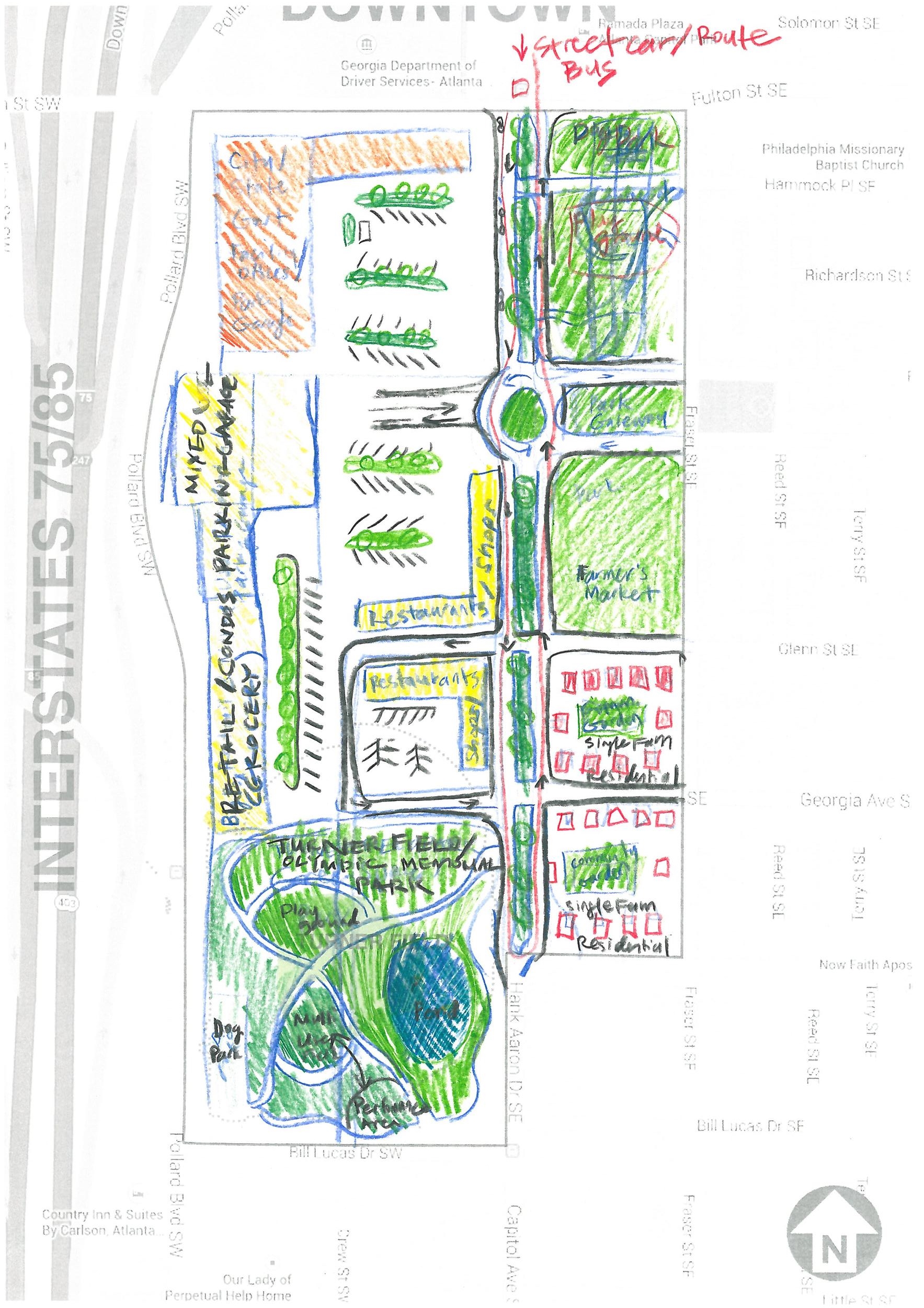

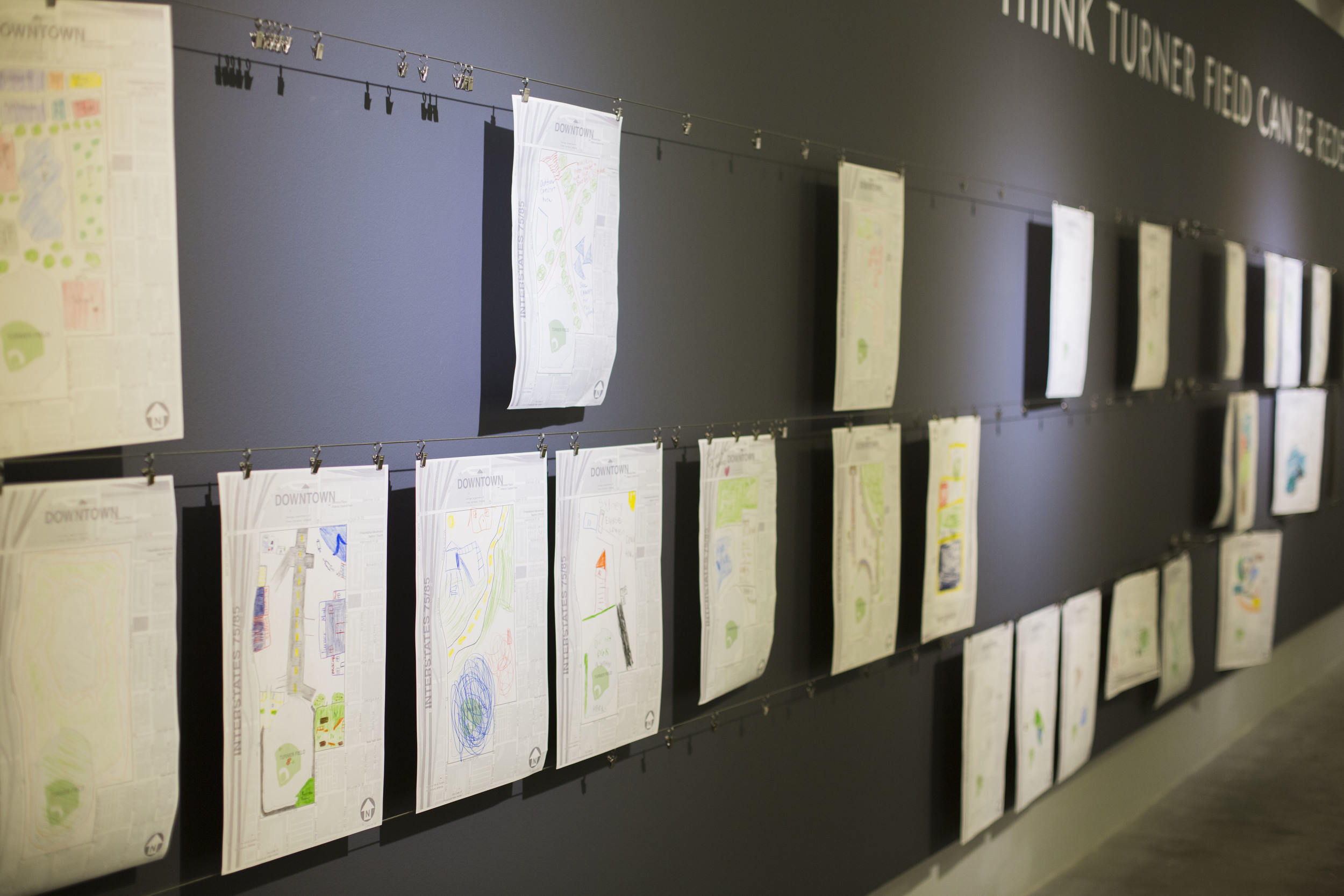

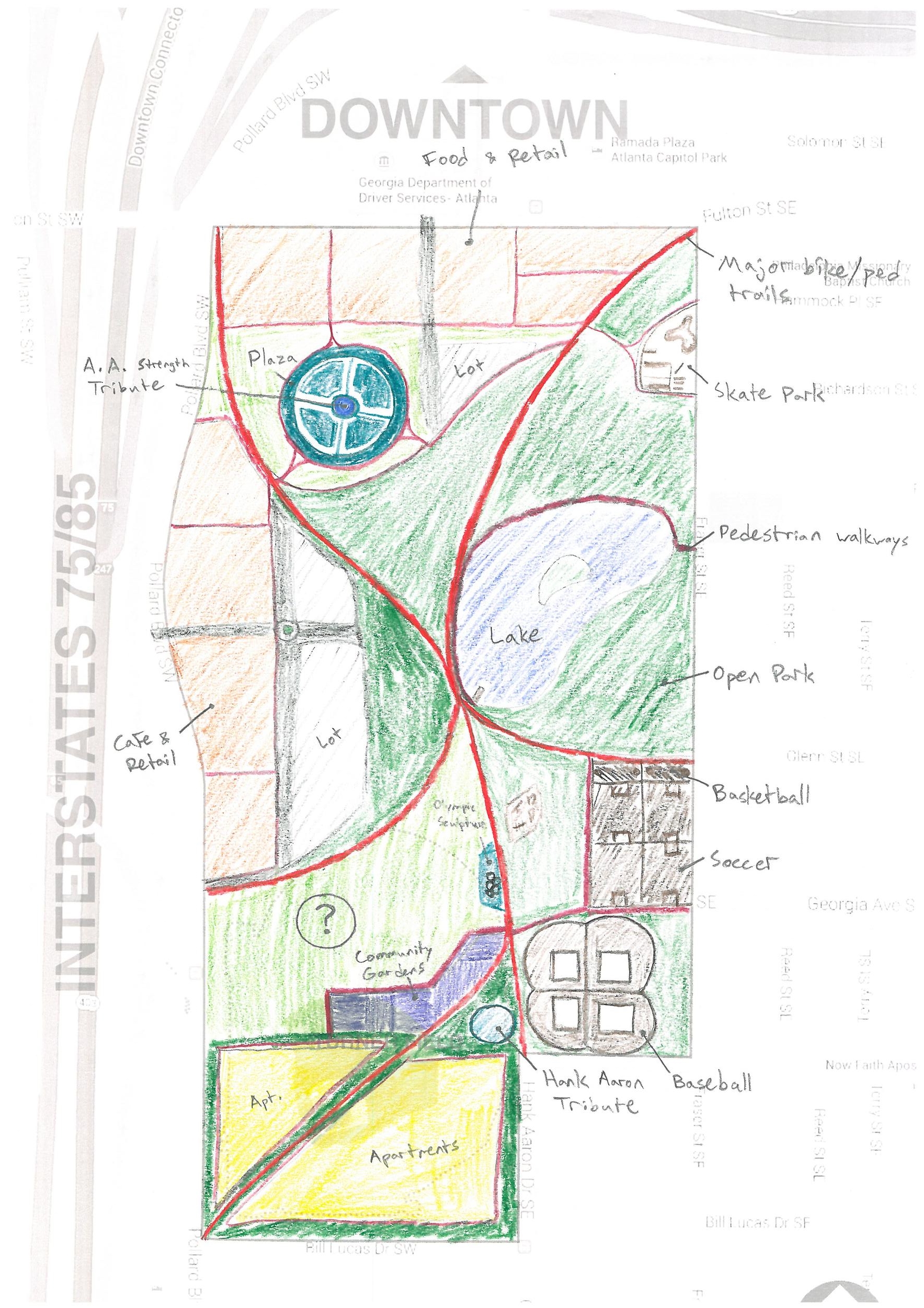

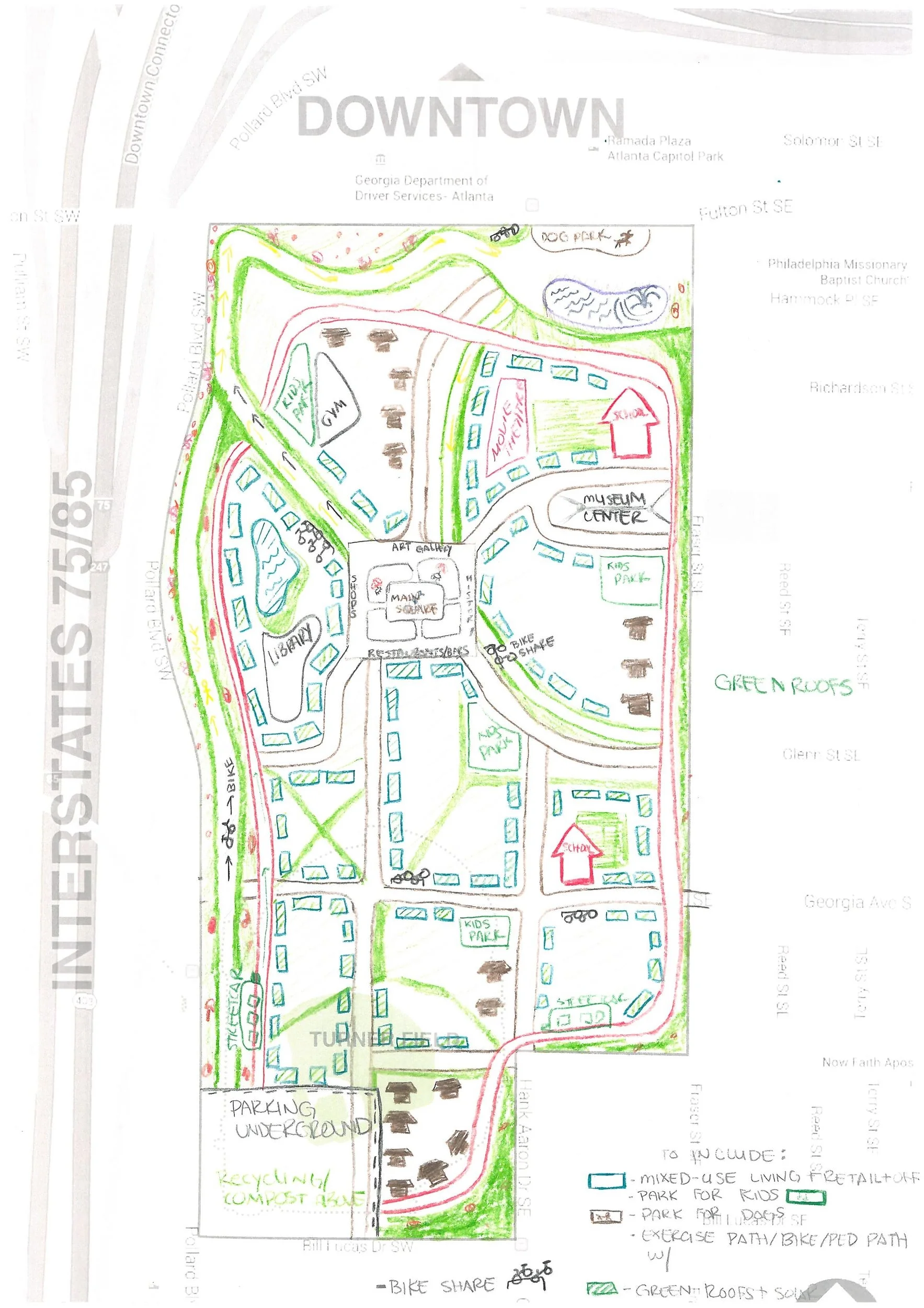

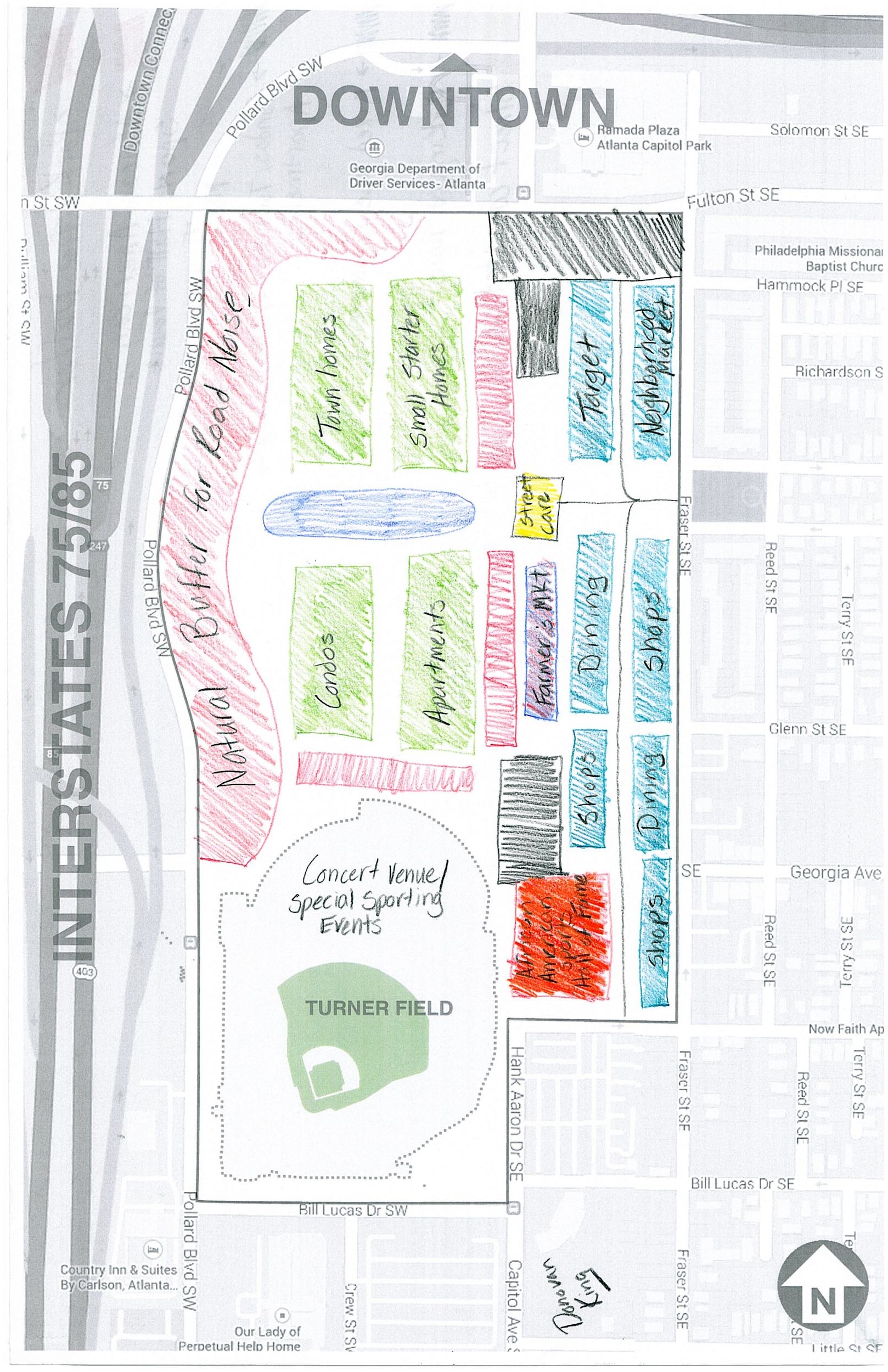

Long tables in the gallery acted as a Design Lab where visitors could get involved in the design process themselves. Plans of the site and colored pencils were provided and visitors were asked to propose a re-design for the site:

Brainstorming and prototyping ideas are important parts of the design process. We invite you to be part of the process by imagining how Turner Field might be redesigned to enhance health and well-being in surrounding neighborhoods.

The activity was wildly popular and we collected hundreds of proposals over the course of the weeks that the exhibition was on show. In this case, our effort to involve visitors in design processes was more successful: the proposals for Turner Field that we collected were shared with the architecture firm Perkins+Will as part of their inclusive planning process for the site.